Answers to five questions about the planetary health diet and the EAT-Lancet Commission.

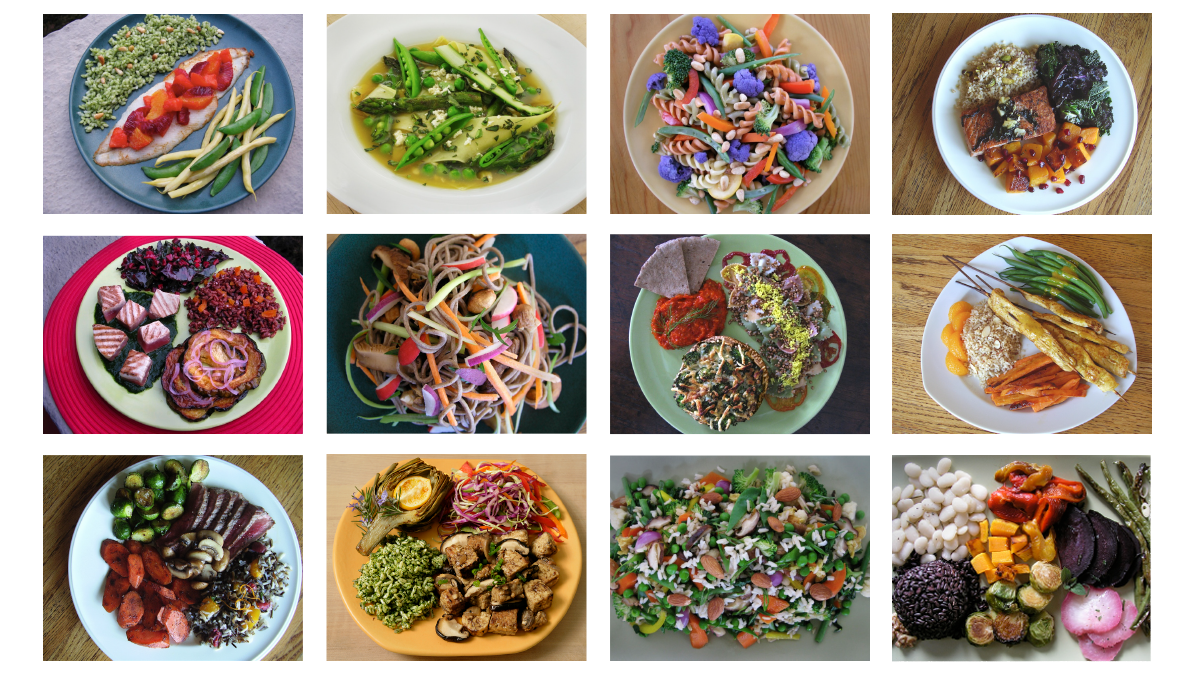

These plates are examples of a planetary health diet – a flexitarian diet, which is largely plant-based but can optionally include modest amounts of fish, meat and dairy foods.

The full report is free to read here.

1. What is the evidence for the planetary health diet?

The Commission used all the best available evidence on diet and human health, and the conclusions are based on consistent evidence from many types of studies (see Supplementary Table 3 in the Commission Appendix). These include randomized controlled feeding studies, randomized trials assessing weight, randomized trials assessing the risk of a specific disease, and long term epidemiology studies involving hundreds of thousands of people over many decades.

Generally, randomized clinical trials are considered to be the strongest type of scientific evidence possible, and the Commission included randomized clinical trials showing benefits of the Mediterranean diet (which provides similar dietary targets to the planetary health diet) for weight control and prevention and recurrence of cardiovascular disease.

In some cases there are only a small number of studies available overall, such as for randomized trials looking at the risk of specific diseases. This is because clinical trials on diet and human health are often not possible because they require people to adhere to an assigned diet for a long time, and there can be ethical considerations. There are also numerous high quality observational studies on diet. However, the main conclusions of the Commission are based on multiple studies of different designs.

2. Is the planetary health diet nutritionally sufficient?

A detailed nutrient analysis of the planetary health diet shows that adoption of the dietary targets would greatly improve the nutrition and health status of most people. The authors estimate that widespread adoption of such a diet would improve intakes of healthy mono and polyunsaturated fatty acids and reduce consumption of unhealthy saturated fats. It would also increase essential micronutrient intake (such as iron, zinc, folate, and vitamin A, as well as calcium in low-income countries), except for vitamin B12 where the EAT-Lancet Commission points out that intakes may be inadequate and supplements or fortified foods may be needed (many foods are already fortified with multiple B-vitamins but not all with B-12).

The Commission did not specifically promote a vegan or vegetarian diet, although these are potentially healthy diets, and instead describes an omnivore diet that includes approximately two servings per day of animal-source foods.

3. Does the diet work for everyone?

The diet is designed to meet nutritional requirements of healthy individuals over 2 years old (with energy intake depending on age, body size, and physical activity), but the authors note that there are also special considerations for adolescent women, and pregnant and breastfeeding women, who often have different nutritional requirements. This is one reason that ranges are given for each dietary component, recognizing the needs and preferences of individuals may differ.

The Commission does not address children less than two years of age because breast feeding is the highest priority and these children have different requirements to support rapid growth. Some premenopausal women may have extra iron requirements because of menstrual losses and taking a supplement is less expensive and without adverse consequences of high red meat intake. The special needs of pregnant and lactating women are recognized and can be met within the ranges of the suggested diet.

4. Did the EAT-Lancet Commission undergo peer review?

The Commission was published following extensive, independent peer review. The Lancet Commissions are subject to the same degree of peer review as all other research content in Lancet journals.

5. How was the EAT-Lancet Commission funded?

The EAT-Lancet Commission is an independent comprehensive assessment of existing science on health and sustainability. It was independently peer reviewed prior to publication in The Lancet medical journal. It was solely funded through the generous support of the Wellcome Trust, which had no role in the writing of the report. In total, 19 Commissioners led the preparation of this report, supported by 18 co-authors; some of whom are EAT employees.

Commissioners received no financial compensation from EAT or Wellcome Trust for their contributions. Commissioners are independent scientists financially supported by their individual institutions. Travel and logistics expenses associated with scientific participation and all costs incurred by EAT, including for staff time, were covered by Wellcome Trust funding.

EAT is an independent, non-profit organization based in Oslo, Norway and founded by the Stordalen Foundation, Wellcome Trust and the Stockholm Resilience Centre. All science-related activities of EAT are financed exclusively from non-profit sources.

Remaining one step

ahead

of the curve.

Five Youth Leaders Who Will Change the World

To celebrate International Youth Day, we are spotlighting the leaders of tomorrow. From India to the US and New Zealand to South Africa, young people are rising to demand greater action on climate change, biodiversity loss, hunger, malnutrition, food waste, plastic pollution, and more.

Reflecting on five years of policy co-creation with youth: the CO-CREATE project

After five years, the CO-CREATE research project “Confronting Obesity: Co-creating policy with youth” has come to end. Reflections on the project’s achievements and sustained impact are shared.